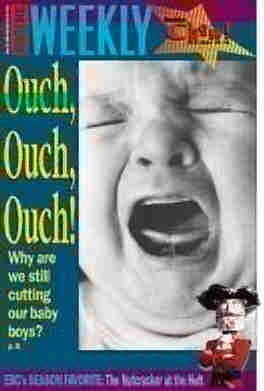

OUCH! OUCH! OUCH!

A Mother's Decision

To circumcise or not? I pondered the question over and over during my nine months of pregnancy. The first time I raised the issue with my midwife, she was shocked I'd even consider it. But she didn't understand the millennia of Jewish guilt I had weighing on me.

"What do you mean I don't understand? I'm Jewish, too!" she yelled at me. It's OK she yelled, she's a good friend of mine. But I figured I was going to have to talk to some other people. No sense in talking to my family. After five grandchildren, my mother had learned to tell her kids "it's your decision" to whatever problems any of us raised regarding parenting. But when I raised this question, I was pretty sure I saw streams of blood dribbling down my mother's chin, she was biting her tongue so hard.

My father was no longer living. If he had been alive, I would have cut, no question. No way I would have been able to explain not circumcising a Jewish male to him.

My sister had circumcised her son. I remember the briss. My brother and I held our tiny eight-day-old nephew while the Rabbi, who was also a moyel (a circumcision performer) said prayers. He gave the baby a piece of gauze soaked in wine to suck on for anesthesia. At the same time, my sister was given a large glass of red wine and led into another room, where she and my mother sat hugging each other on the couch, crying.

My father, still living then, held his grandson still. The moyel did the circumcision. The baby screamed. Every single man in the room was standing with his legs slightly apart, his hands folded in front of his crotch, subconsciously protecting himself.

We brought the baby to his mother. She put him to her breast. They both stopped crying. We ate cold cuts. I didn't want to know the sex of my child until it was born. I've always liked surprises. Even so, for several months I hoped for a girl, just so I could avoid making the big decision.

But then I got real, so I started talking to people about whether or not to circumcise. I had read a lot of material against circumcision in the past. Several articles by a Jewish midwife in Portland laid out the argument for performing less radical circumcisions, slicing just a small portion of the tip of the foreskin, and for using anesthesia during the operation. During a briss, done at home, she even advocated for sneaking in some topical anesthetic and applying it to the baby's penis before the moyel could see. Or she said, shop around for a moyel who believed in anesthesia.

Then I remembered something strange that had happened years before when I lived in Kenya. One night, after hanging out at a local bar with some friends, one guy just asked me out of the blue if I was circumcised. I had no idea what he was talking about. Later, I was to edit a lengthy essay on female circumcision and learn about the international women's movement to ban the practice - widely performed throughout Africa and parts of the Middle East - and its extreme brutality.

So why should male circumcision be considered any less brutal, I wondered? True, some forms of female circumcision are so extreme they go way beyond what we do to our infant boys. But I began to think the principle was the same.

One day a former student of mine called me up. She wanted some advice regarding a job and wanted to take me out to discuss it. During lunch, she asked me if I was going to do a circumcision if I had a boy. I told her I didn't know. She was dumbfounded.

"They don't even do that in Israel anymore!" she said.

They don't?

"On the kibbutz I was on they just shave a carrot as a ritual circumcision," she said.

I never bothered to confirm her story's veracity. I wanted to believe her. I picked up the check. My next step was calling two rabbis. I asked each of them the same question. Could my son make a Bar Mitzvah if he wasn't circumcised? They both gave the same answer:

"As far as I know, nobody looks."

I went searching for a pediatrician. I had many referrals. We've got great doctors in this town. I narrowed down my choices. I called one to see if I could meet her, but she was busy and suggested we do an interview over the phone.

She told me when I would need to bring the baby in, when vaccinations would be due, and more. She was a little surprised when I told her I was having the baby at home, but she collected herself. Then she told me she was also trained to do circumcisions, if my baby turned out to be a boy.

"I'm not going to circumcise him," I told her.

She paused. Then the doctor I had never before met just couldn't hold back.

"You mean to tell me, Ari Seligmann, that your family isn't going to freak out if you don't have a briss?" I laughed. I liked her.

"Well, they're 3,000 miles away, I guess they can freak out," I told her.

Ironically, a week after my son was born, much of my family was in town. We were having a barbecue in the backyard. Knowing what was on my mother's and sister's minds, and figuring they were talking about it behind my back, I brought up the subject.

"Today's the eighth day," I said, rocking my son. "I guess this barbecue is his briss."

"Maybe we should drink a glass of wine and toast or something," my mother said.

It did feel odd not to mark the day in some way.

Suddenly, my son's father, who's not Jewish and had been surprisingly quiet on the issue up until now, picked up a sweet potato that was laying on the table. It had a rather extended end.

"Here ya go! Here's your circumcision!" he said, raising a butcher knife and lopping the end of the potato off so that the end went hurling through the air, landing on the lawn.

My family was stunned into silence.

He held up the potato.

"It's a sacrificial yam," he said.

My mother took the baby from my arms, cradled him and looked into his face.

"Boy, are you one lucky kid," she said.

Back to Mothers' Stories